Understanding Route Grades

Yosemite Decimal System

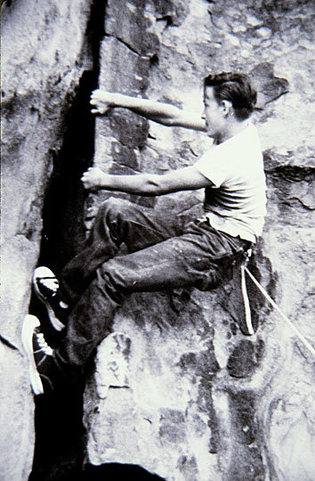

Roual Robbins on Open Book, Tahquitz Rock, CA. First 5.9 free ascent.

So, your friend says, "Don't worry, it's just a 5.7, you'll be fine. Get psyched, it has four stars!" You raise your eyebrow. "A five what now? and wasn't I done with gold stars in fifth grade??" Relax. Your climber buddy is referring to the Yosemite Decimal System(YDS), or the rubric that we use in the USA to categorize climbs based on their difficulty.

The Yosemite Decimal System has 5 classes ranging from Class 1 to Class 5, which are used to classify all terrain according to the difficulty for humans to travel across with no mechanical advantage (like, let's say, a four-wheeler). Class 5 is where rock climbing begins and is subdivided into various levels. The climbing subdivisions for the Yosemite Decimal System were first implemented at Tahquitz rock in Southern California by a few important early climbers including Royal Robbins (photo) and Yvon Chouinard (founder of Patagonia and Black Diamond) amongst others. Later, both climbers went on to climb prolifically in Yosemite making many famous first big wall ascents, breaking many of the technical barriers in the sport, and establishing important ethical guidelines for climbers. The Yosemite Decimal System describes routes by Class (difficulty), Grade (length), and Protection (safety). All are described below. Yosemite Decimal System - Class: Class 1- Easy walking. You are in a mall, on a bike path, or walking with your arthritic grandmother. If you fall, you were either pushed or you are dumb. Class 2 - A bit steeper, uneven ground. You are on a hiking trail, a sloping hill, or walking on a rocky beach. If you fall you might hurt yourself, but nothing serious. Class 3 - We are getting serious here. You are scrambling up some large boulders where using your hands may help you to ascend. If you fall, you will probably hurt yourself and possibly even break a bone. Ropes are generally not recommended and would look silly in this terrain. Class 4 - We are getting close to rock climbing territory here. You are using your hands and feet to ascend. You probably have good exposure, meaning that a fall from high would likely result in serious injuries. It is recommended to use a rope on some Class 4 terrain and to ascend using mountaineering techniques that will not be described here. You are probably thinking, "Oh crap, if I fall, it's going to really suck....but I'm not going to fall. This feels pretty easy." Class 5- Now we are rock climbing. You are on vertical or nearly vertical terrain that requires a rope and the use of hardware or anchors to ascend safely. You are using technical maneuvers with both hands and feet to ascend. If you fall without a rope or protection, you are either dead or VERY seriously injured. |

At a Glance:

Yosemite Decimal System Class 1: flat ground, easy walking Class 2: Inclined and uneven, more difficult walking Class 3: Very uneven and inclined, may be using hands to ascend Class 4: Hands and feet necessary to easily ascend. Falling would be serious. Class 5: Rock climbing. Technical maneuvers to ascend. A fall without a rope would result in serious injury or death. Subclasses: 5.1 - 5.15. After 5.10, subdivided further as a,b,c,d. Grade I: 1-2 hours Grade II: < half day Grade III: Half Day Grade IV: Full day Grade V: Two days Grade VI: Multiple days Grade VII: More than a week G: Well protected, safe. PG: Some run out moves and risk. PG-13: Moderately risky with several unprotected moves. R: Unprotected stretches of the climb and risky moves. Falls in these unprotected areas could result in serious injury. X: Very dangerous and difficult to protect. Climb at your own risk. Bouldering "V" Scale easiest to most difficult: V0 - V16 Ratings subdivided with + and - signs. ex: V3+ is easier than a V4- V0 should be the rough equivalent of a 5.10d, though in recent years more routes are being graded softer. |

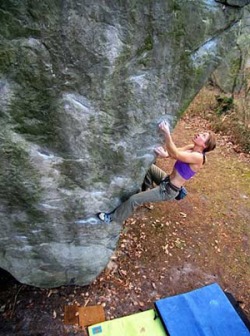

Chris Sharma, Jumbo Love 5.15b

Now that we are in Class 5, the ratings get subdivided using a system of decimals, numbers and letters. 5.1 is the first division, followed by 5.2, followed by 5.3. As the number following the decimal increases, so does the difficulty of the terrain. A route is rated according to the difficulty of the most difficult move (a.k.a. the crux). Unlike in a gym, the rock outside is not uniform or tailored for the human body. This means that you can climb a route that is mostly 5.9 but has one or two moves that are 5.11. It is important to note this because you may be standing at the base of what your guide book calls a 5.12, but you look up and it looks totally doable and in your ability level. Be wary of jumping on something based on appearances like this, however, because you may find yourself needing to bail off the route 3/4s of the way up because you cannot get past the crux.

When the Yosemite Decimal System was first introduced, it was believed that 5.9 was the hardest possible grade. Royal Robbins climbed the first 5.9 at Tahquitz on a classic route called "Open Book." As climbing equipment got lighter and better, however, the grades increased and the Yosemite Decimal System expanded to include 5.10, 5.11, etc.

As more and more 5.10 and 5.11 routes were created by pioneer climbers in the 1960s, the climbing community realized that further subdivisions were necessary to delineate various levels of difficulty within each level. These subdivisions are annotated with letters: 5.10a, 5.10b, 5.10c, and 5.10d. The system is intuitive. For example, 5.10a is easier than 5.10d. After 5.10d, you move into the 5.11 rating, which is further subdivided into a, b, c, d. So on and so forth.

Ratings are established at first by the climber who made the first ascent of the route, and then are adapted as the climbing community creates a consensus on the difficulty. This method becomes controversial at the forefront of climbing where the most expert climbers are truly pushing the limits of the sport. At such high class ratings, few other climbers in the world can repeat certain climbs, and consensus is difficult to achieve.

It is generally accepted that 5.15b is the hardest route ever climbed (Jumbo Love in 2008 and Neanderthal in 2009*see photo*, both by Chris Sharma), though there is a claim on a 5.15c route in Spain that is waiting consensus from the climbing community. If you want to see what it looks like to climb one of the hardest routes in the world, here is a video of Chris Sharma climbing Realization (5.15a) (see video below), the first route to break the 5.15 barrier in 2001. Since then, several other 5.15s have been climbed and the limits of climbing continue to be pushed.

A note on Class: The class ratings are quite subjective and vary from crag to crag. A particular 5.11 climb with big, reachy moves may be a breeze for a "knuckle dragger" (i.e. a climber with big wing span) while the same climb is near impossible for someone of small stature, even if the smaller statured climber is more fit and experienced. Certain climbs are simply suited to different climbers. That same knuckle-dragger will most likely struggle up a balancy and delicate climb that the smaller climber flies up. The perfect example of this is a story a very experienced climber once told me. He was working on a 5.12 finger crack in Joshua Tree all morning and kept falling off at the "crux" (or hardest point). After falling off again, his 9-year-old nephew who had been watching asked to try. After getting harnessed up, the child basically ran up the route, hardly even pausing at the crux. Clearly, it was a distinction of finger size rather than skill and experience that got the child up the route. Moral of the story: Don't sweat the ratings! They are subjective and meaningless. Use them as a guide to get on routes that you will find enjoyable and to stay off routes that will be too dangerous for your ability level.

When the Yosemite Decimal System was first introduced, it was believed that 5.9 was the hardest possible grade. Royal Robbins climbed the first 5.9 at Tahquitz on a classic route called "Open Book." As climbing equipment got lighter and better, however, the grades increased and the Yosemite Decimal System expanded to include 5.10, 5.11, etc.

As more and more 5.10 and 5.11 routes were created by pioneer climbers in the 1960s, the climbing community realized that further subdivisions were necessary to delineate various levels of difficulty within each level. These subdivisions are annotated with letters: 5.10a, 5.10b, 5.10c, and 5.10d. The system is intuitive. For example, 5.10a is easier than 5.10d. After 5.10d, you move into the 5.11 rating, which is further subdivided into a, b, c, d. So on and so forth.

Ratings are established at first by the climber who made the first ascent of the route, and then are adapted as the climbing community creates a consensus on the difficulty. This method becomes controversial at the forefront of climbing where the most expert climbers are truly pushing the limits of the sport. At such high class ratings, few other climbers in the world can repeat certain climbs, and consensus is difficult to achieve.

It is generally accepted that 5.15b is the hardest route ever climbed (Jumbo Love in 2008 and Neanderthal in 2009*see photo*, both by Chris Sharma), though there is a claim on a 5.15c route in Spain that is waiting consensus from the climbing community. If you want to see what it looks like to climb one of the hardest routes in the world, here is a video of Chris Sharma climbing Realization (5.15a) (see video below), the first route to break the 5.15 barrier in 2001. Since then, several other 5.15s have been climbed and the limits of climbing continue to be pushed.

A note on Class: The class ratings are quite subjective and vary from crag to crag. A particular 5.11 climb with big, reachy moves may be a breeze for a "knuckle dragger" (i.e. a climber with big wing span) while the same climb is near impossible for someone of small stature, even if the smaller statured climber is more fit and experienced. Certain climbs are simply suited to different climbers. That same knuckle-dragger will most likely struggle up a balancy and delicate climb that the smaller climber flies up. The perfect example of this is a story a very experienced climber once told me. He was working on a 5.12 finger crack in Joshua Tree all morning and kept falling off at the "crux" (or hardest point). After falling off again, his 9-year-old nephew who had been watching asked to try. After getting harnessed up, the child basically ran up the route, hardly even pausing at the crux. Clearly, it was a distinction of finger size rather than skill and experience that got the child up the route. Moral of the story: Don't sweat the ratings! They are subjective and meaningless. Use them as a guide to get on routes that you will find enjoyable and to stay off routes that will be too dangerous for your ability level.

Yosemite Decimal System - Grades:

The Yosemite Decimal System also includes an optional Grade rating. The grades, annotated with roman numerals, indicate the length of the climb, and are intended to help climbers properly prepare for their ascent. The YDS Grades are listed below:

Grade I: 1-2 hours

Grade II: < half day

Grade III: Half Day

Grade IV: Full day

Grade V: Two days

Grade VI: Multiple days

Grade VII: More than a week

Yosemite Decimal System - Protection Ratings

The Yosemite Decimal System Protection Ratings tell climbers how well the route is protected using either fixed or placed protection. This rating, combined with the class rating (5.9, 5.10a, etc) helps the climber assess if the climb is worth the risk and if a fall is likely according to the climber's ability level. The ratings are as follows:

G: good, solid protection. If using proper climbing techniques, the climb is very safe.

PG: Pretty good protection. A few moves might leave the climber exposed to a dangerous fall, but overall the climb is safe.

PG-13: Shaky protection. The climber may have to climb high above the last piece of protection, but a fall will most likely not be fatal or cause serious injury.

R: Poor protection, or "runout." The climber will have to climb very high above his/her protection, and a fall from such location will result in death or serious injury. Make sure you have health insurance before climbing!

X: Extremely dangerous. Very, very poor protection available. Do not fall - ever - because a fall will likely cause death.

The Yosemite Decimal System also includes an optional Grade rating. The grades, annotated with roman numerals, indicate the length of the climb, and are intended to help climbers properly prepare for their ascent. The YDS Grades are listed below:

Grade I: 1-2 hours

Grade II: < half day

Grade III: Half Day

Grade IV: Full day

Grade V: Two days

Grade VI: Multiple days

Grade VII: More than a week

Yosemite Decimal System - Protection Ratings

The Yosemite Decimal System Protection Ratings tell climbers how well the route is protected using either fixed or placed protection. This rating, combined with the class rating (5.9, 5.10a, etc) helps the climber assess if the climb is worth the risk and if a fall is likely according to the climber's ability level. The ratings are as follows:

G: good, solid protection. If using proper climbing techniques, the climb is very safe.

PG: Pretty good protection. A few moves might leave the climber exposed to a dangerous fall, but overall the climb is safe.

PG-13: Shaky protection. The climber may have to climb high above the last piece of protection, but a fall will most likely not be fatal or cause serious injury.

R: Poor protection, or "runout." The climber will have to climb very high above his/her protection, and a fall from such location will result in death or serious injury. Make sure you have health insurance before climbing!

X: Extremely dangerous. Very, very poor protection available. Do not fall - ever - because a fall will likely cause death.

Star Ratings

Necessary Evil, FIVE STARTS, Apple Valley, CA

In addition to the Yosemite Decimal System ratings, you will oftentimes see a "star" rating in climbing guide books. The stars work just like they do for movie or restaurant ratings - they tell you how awesome (or un-awesome) the route is to climb. 5 stars means that the route feels absolutely spectacular to climb. You will have interesting moves, great views, and sweet protection. 1 star means that the route is not so good. It may have some very awkward moves or you might have to climb through a bush on a ledge, or the bolts may be so horribly positioned that clipping them becomes harder than doing the climbing.

The photo on the left is of Necessary Evil in Apple Valley, CA. The route is 5.10b and has FIVE STARS! The route is so much fun to climb, it is not uncommon to hear climbers screaming, "This is amazing!" while making the ascent.

The photo on the left is of Necessary Evil in Apple Valley, CA. The route is 5.10b and has FIVE STARS! The route is so much fun to climb, it is not uncommon to hear climbers screaming, "This is amazing!" while making the ascent.

The Bouldering "V" or "Hueco" Scale

Dave Gaham on The Island, V15, Fontainbleu, France

The most widely used system for rating bouldering problems in the USA is the "V" or "Hueco" Scale. Named for pioneer boulderer, John "Vermin" Sherman who climbed the amazing boulders of Hueco Tanks, TX, the V Scale denotes the level of difficulty of a boulder problem. *Note that when climbing, you climb "routes," when bouldering, you climb "problems."

The system is simple and intuitive. V0 is the easiest and the scale increases by integers up to V16, the hardest rating yet completed. Oftentimes, a "+" or a "-" will indicate if the problem is on the easier or harder side of a certain grade (Ex: A V2+ is a harder V2, but does not quite qualify as a V3). Because bouldering takes place close to the ground and tends to be much shorter, requiring less stamina, the rating system starts at a much harder grade than the Yosemite Decimal System. The difficulty of a V0, a beginning boulder problem, is comparable to a 5.10d, a moderate to difficult climb.

Check out this website to watch some videos of some of the hardest bouldering problems in the world being tackled.

The system is simple and intuitive. V0 is the easiest and the scale increases by integers up to V16, the hardest rating yet completed. Oftentimes, a "+" or a "-" will indicate if the problem is on the easier or harder side of a certain grade (Ex: A V2+ is a harder V2, but does not quite qualify as a V3). Because bouldering takes place close to the ground and tends to be much shorter, requiring less stamina, the rating system starts at a much harder grade than the Yosemite Decimal System. The difficulty of a V0, a beginning boulder problem, is comparable to a 5.10d, a moderate to difficult climb.

Check out this website to watch some videos of some of the hardest bouldering problems in the world being tackled.

International Grades

Lisa Rands on Megalilth, E9, Fontainbleau, France

Fully going into the various international grading systems is beyond the scope of this website. In the USA, we generally use the Yosemite Decimal System described above. If you travel out of country or read about routes in other countries, you will invariably see ratings that look like "9a+" (France/Spain) or "7B/E10" (UK). Check out this website to see a full chart comparison of the various grade systems used throughout the world, including the Yosemite Decimal System and the V Scale.