Placing Passive Protection

|

Passive protection is protection that does not actively cam in the rock, and does not have moving parts. Contrarily, a piece that "cams" is a piece that applies increasing pressure outward, against the walls of crack, as it is pulled downward; this is also known as Active Protection. Passive protection relies on constrictions in cracks to hold it in place. The most common types of passive protection are nuts or stoppers. Hexagonal wedges (hexes), Tri-Camming Units (tri-cams), and even Spring Loaded Camming Devices (or SLCDs or cams) can all be used as either active or passive protection. These pieces must be placed differently according to the application desired. Become familiar with each type of piece and its various placements and applications. Big Bros, spring-loaded tube chock, are another form of passive protection used in large cracks (mainly > 6.5 inches). They are incredibly strong and a great feat of engineering, but not as widely used, so we will not focus on them here.

|

At a Glance:

Your Passive Pro Rack: Nuts a.k.a. Stoppers Hexes Big Bros SLCD (Cams) *placed passively Tri-Cams *placed passively Pros of passive pro: Bomber Reliable Quick to place Lighter than cams Durable equipment Cheaper than cams Cons of passive pro: Susceptible to rope drag Pieces hard to remove Steep learning curve Constriction in rock necessary |

Passive protection is incredibly strong, durable, and reliable. A solid nut placement in a crack is bomber enough to take a big fall from a lead climber. A downside to passive protection is that it is more likely to pop out with rope drag. It is always best to extend nut or hex placements with a quickdraw or an extended alpine draw, according to the anticipated direction of the climb. Another downside is that nuts can be extremely difficult to remove from the rock, especially if the leader fell or sat on the piece. Black Diamond and Metolius both make nut tools, which are designed to help the second remove difficult placements.

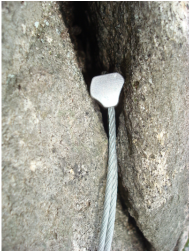

Example Placements:

|

So what makes a good passive protection placement?

Other considerations on Passive Protection:

For a more in-depth discussion of what makes a good passive placement, we recommend John Long's book Climbing Anchors. He goes into great depth about what makes for good protection. |