Types of Climbing

"It doesn't make a huge difference to me whether I'm on bolts, or on gear, or on pads, or whatever. It's whether you're climbing or not, and once you're climbing you just go out there and do your best and make it happen and pray for the best." - Alex Honnold

Traditional Climbing/ Free Climbing

Traditional climbing is considered the purest form of climbing. The climber approaches a rock, decides to climb it and protects his falls using the gear he carries. His partner climbs second and removes all the gear, leaving the rock unaltered. "Free ascents" are further considered to be the purest form within traditional climbing. To "free climb" a route, the climber places gear in the rock only for safety, never resting or pulling up on it, except at anchors. If the climber falls on the gear, the ascent is not considered a "free ascent." He must lower down to the bottom of the climb and attempt again with no falls. So when people say that Lynn Hill was the first person to free climb the Nose of El Cap in a day, this means that she placed gear, but finished each pitch of the climb without falling or using the gear in any way to assist her (such as in Aid Climbing). No one repeated Hill's free ascent on the Nose in a single day until Tommy Caldwell and Beth Rodden repeated the climb ten years later.

Watch Lynn Hill on the historic ascent below: |

At a Glance:

|

Also check out this video of Sonnie Trotter free climbing (possibly) the hardest trad route ever climbed, the 5.14 b/c Cobra Crack in Squamish, BC.

Aid Climbing

Aid Climbing is a form of climbing in which the leader uses the placed protection to pull up or aid in his/her ascent. This form of climbing is utilized when free climbing is impossible or out of the climber's ability level. Aid is often used on long, big wall routes where mental and physical stamina is required, and where there may be vast expanses of rock face between protectable crack systems. Aid climbing allows climbers to connect these crack systems safely and bypass sections of a climb that are out of their ability range. The Changing Corners pitch on the Nose (featured above in the Lynn Hill video) was thought impossible to climb "free" and climbers aided this pitch for years. Lynn Hill and Tommy Caldwell are the only climbers to climb the pitch free without the aid of their gear.

Sport Climbing

Stripped-down and fast-paced, sport climbing is the quickest way to climb rock while placing your own protection. The sport style tests a climber's gymnastic abilities and strength more than equipment expertise. Compared to traditional climbing (discussed above), a sport climber spends very little energy protecting the climb and more energy on performing difficult moves.

Unlike traditional climbing where the leader and belayer are the only players involved in climbing a route, in sport climbing, there is a third player, the route-setter who at one time defined the route. The route-setter originally climbed the route and used a mechanical drill to place bolts in the rock. These bolts are metal anchors similar to those used in construction, and affixed with bolt hanger loops. The bolts are fixed anchors and remain in place for future climbers to use. The safety system in sport climbing is comprised of quick draws (two carabiners connected with webbing), dynamic rope, a belay device and climbing harnesses. When the climber begins, she is completely unprotected and off belay until she reaches the first bolt (usually 10-15 feet off the ground). Once there, she attaches one of her quick draws then clips the rope through the quick draw. She is now protected and on belay. As she climbs onward she continues to clip into the bolts that follow the "line" of the route. If she falls while climbing, her belay partner will arrest the rope using his belay device, causing the rope to pivot around the last bolt clipped. It is far quicker and easier to clip a quickdraw into a sport bolt than to place a piece of traditional climbing protection (e.g. a cam or a nut). Sport climbing, as the name implies, emphasizes the athleticism of ascending a rock face and allows expert rock climbers to truly test their climbing abilities. It is also far less technical than traditional climbing, so it makes a great introduction to leading for beginner and intermediate climbers.

The advent of bolts also opened up many rock faces that were previously unclimbable because they lack cracks in which to place traditional gear. Sport climbers are pushing the limits of climbing and of human physical ability. Nearly every year a climber ascends a route that was previously thought impossible. It is inspirational and mesmerizing to watch what the best sport climbers in the world can do.

Check out this video of Chris Sharma projecting his next 5.15 sport climb, Pachamama 5.15, in Spain. It will give you a good taste for the level of climbing that bolts opened up.

Unlike traditional climbing where the leader and belayer are the only players involved in climbing a route, in sport climbing, there is a third player, the route-setter who at one time defined the route. The route-setter originally climbed the route and used a mechanical drill to place bolts in the rock. These bolts are metal anchors similar to those used in construction, and affixed with bolt hanger loops. The bolts are fixed anchors and remain in place for future climbers to use. The safety system in sport climbing is comprised of quick draws (two carabiners connected with webbing), dynamic rope, a belay device and climbing harnesses. When the climber begins, she is completely unprotected and off belay until she reaches the first bolt (usually 10-15 feet off the ground). Once there, she attaches one of her quick draws then clips the rope through the quick draw. She is now protected and on belay. As she climbs onward she continues to clip into the bolts that follow the "line" of the route. If she falls while climbing, her belay partner will arrest the rope using his belay device, causing the rope to pivot around the last bolt clipped. It is far quicker and easier to clip a quickdraw into a sport bolt than to place a piece of traditional climbing protection (e.g. a cam or a nut). Sport climbing, as the name implies, emphasizes the athleticism of ascending a rock face and allows expert rock climbers to truly test their climbing abilities. It is also far less technical than traditional climbing, so it makes a great introduction to leading for beginner and intermediate climbers.

The advent of bolts also opened up many rock faces that were previously unclimbable because they lack cracks in which to place traditional gear. Sport climbers are pushing the limits of climbing and of human physical ability. Nearly every year a climber ascends a route that was previously thought impossible. It is inspirational and mesmerizing to watch what the best sport climbers in the world can do.

Check out this video of Chris Sharma projecting his next 5.15 sport climb, Pachamama 5.15, in Spain. It will give you a good taste for the level of climbing that bolts opened up.

Ethics, History and Controversy

When sport bolts were first introduced into the climbing world, it was a wild controversy. Fist fights at Camp 4 in Yosemite and at mountaineering club meetings were not uncommon. Clean climbing advocates at the time believed that if you didn't place your own protection on the route, it wasn't climbing. If there was no way to protect yourself on a rock face (i.e. no cracks to place gear into), then you either manned-up and climbed with what protection you could find, or you didn't climb it at all. Using fixed protection (i.e. bolts) was absolutely out of the question and was considered cheating by many.

In 1970 Warren Harding (photo) and Dean Caldwell made the first ascent of the "Wall of Early Morning Light" on El Cap in Yosemite, a route that had long been coveted by many other climbers. The route was incredibly difficult and involved crossing a large, blank face with no cracks for placing traditional climbing gear. Climbing it without bolts, was on par with a death wish. Harding and Caldwell, however, brought a mechanical drill with them and laboriously drilled bolts into the face to protect the climbing. Using heavy equipment and working slowly, they eventually summited after 27 days of hanging on the face. They were on the rock for so long that the Park Service sent a rescue party on day 22, at which Harding and Caldwell shouted profanity and threw cheap wine. Though the climb was celebrated by many, it also caused much contention in the climbing community due to the team's heavy reliance on bolts. Almost immediately after Harding and Caldwell had climbed (and bolted) the previously impossible to protect faces of the route, Royal Robbins (one of the more prominent clean climbing advocates) climbed the route and destroyed their bolts in protest to what he saw as the impure form of protection.

Today, sport climbing and the use of bolts is widely accepted. The advent of bolts, and their slow acceptance into the climbing community, opened up many rock faces that previously would have been virtual suicide to climb. Lynn Hill, legendary female climber, praises this advancement for removing some of the risk and the dare-devil, macho aspects of the sport that she found in the early Yosemite days. Rock faces with little or no cracks to place traditional climbing protection could now be bolted and ascended by climbers in relative safety. With the protection already fixed into the rock, climbers could carry less gear and could make their clips much quicker. With less weight to carry and easier methods of protecting their falls, climbers could climb much harder routes. To this day, the hardest route climbed is a sport route, and that is unlikely to change.

Though now openly accepted as a respectable form of climbing, there are ethics regarding where bolts can and cannot be placed. Placing bolts on or near a crack system is near heresy in most climbing communities. Cracks can be properly protected using traditional gear, and placing fixed anchors (bolts) where traditional placements are possible is considered degrading to the purity of the rock and the sport. In the first days of bolting, it was also considered poor form to rappel down from the top of the rock and place bolts with a mechanical drill. In those days, you had to climb the route from the ground up and drill in your protection as you went (a la Harding/Caldwell). Today, the rules have expanded to accept the method of rappelling and drilling, which allows route-setters to place bolts on wildly difficult climbs and to truly push the limits of the sport.

Though many of the climbing "rules" have expanded to accept techniques like bolting from above, there remains one standard that continues to be considered sacred: absolutely no chipping holds. Some climbers throughout history have been known to chip holds in routes in order to climb what they believed to be unclimbable sections. These climbers are usually persecuted, ridiculed, and frowned upon mercilessly until they are forced off the rock with their tails between their legs. One such climber was Ray Jardine, a man who became obsessed with free-climbing the Nose on El Cap during the 1970s. The famous route had been climbed numerous times, but always by utilizing "Aid Climbing" techniques (see below) to get past the most difficult sections. Jardine dreamed of free climbing every section from the valley floor to the summit. After years of trial and failure on the route, he decided to try a traverse across a blank face that would connect two good crack systems. In order to complete the traverse, Jardine used a chisel to form hand and foot holds into the rock. Although he was then able to "free climb" the route as he dreamed, he was ridiculed out of Yosemite Valley for his poor form and blatant cheating. Today, his techniques continue to be regarded as extremely poor form. The first climber to truly free climb the Nose and achieve Jardine's dream was Lynn Hill. Her critique of Jardin is also a poignant reflection on the art of traditional free climbing: "[Jardine] failed to recognize that the spirit of free climbing is about adapting one's personal capacities and dimensions to the natural features of the rock, not the other way around."

In 1970 Warren Harding (photo) and Dean Caldwell made the first ascent of the "Wall of Early Morning Light" on El Cap in Yosemite, a route that had long been coveted by many other climbers. The route was incredibly difficult and involved crossing a large, blank face with no cracks for placing traditional climbing gear. Climbing it without bolts, was on par with a death wish. Harding and Caldwell, however, brought a mechanical drill with them and laboriously drilled bolts into the face to protect the climbing. Using heavy equipment and working slowly, they eventually summited after 27 days of hanging on the face. They were on the rock for so long that the Park Service sent a rescue party on day 22, at which Harding and Caldwell shouted profanity and threw cheap wine. Though the climb was celebrated by many, it also caused much contention in the climbing community due to the team's heavy reliance on bolts. Almost immediately after Harding and Caldwell had climbed (and bolted) the previously impossible to protect faces of the route, Royal Robbins (one of the more prominent clean climbing advocates) climbed the route and destroyed their bolts in protest to what he saw as the impure form of protection.

Today, sport climbing and the use of bolts is widely accepted. The advent of bolts, and their slow acceptance into the climbing community, opened up many rock faces that previously would have been virtual suicide to climb. Lynn Hill, legendary female climber, praises this advancement for removing some of the risk and the dare-devil, macho aspects of the sport that she found in the early Yosemite days. Rock faces with little or no cracks to place traditional climbing protection could now be bolted and ascended by climbers in relative safety. With the protection already fixed into the rock, climbers could carry less gear and could make their clips much quicker. With less weight to carry and easier methods of protecting their falls, climbers could climb much harder routes. To this day, the hardest route climbed is a sport route, and that is unlikely to change.

Though now openly accepted as a respectable form of climbing, there are ethics regarding where bolts can and cannot be placed. Placing bolts on or near a crack system is near heresy in most climbing communities. Cracks can be properly protected using traditional gear, and placing fixed anchors (bolts) where traditional placements are possible is considered degrading to the purity of the rock and the sport. In the first days of bolting, it was also considered poor form to rappel down from the top of the rock and place bolts with a mechanical drill. In those days, you had to climb the route from the ground up and drill in your protection as you went (a la Harding/Caldwell). Today, the rules have expanded to accept the method of rappelling and drilling, which allows route-setters to place bolts on wildly difficult climbs and to truly push the limits of the sport.

Though many of the climbing "rules" have expanded to accept techniques like bolting from above, there remains one standard that continues to be considered sacred: absolutely no chipping holds. Some climbers throughout history have been known to chip holds in routes in order to climb what they believed to be unclimbable sections. These climbers are usually persecuted, ridiculed, and frowned upon mercilessly until they are forced off the rock with their tails between their legs. One such climber was Ray Jardine, a man who became obsessed with free-climbing the Nose on El Cap during the 1970s. The famous route had been climbed numerous times, but always by utilizing "Aid Climbing" techniques (see below) to get past the most difficult sections. Jardine dreamed of free climbing every section from the valley floor to the summit. After years of trial and failure on the route, he decided to try a traverse across a blank face that would connect two good crack systems. In order to complete the traverse, Jardine used a chisel to form hand and foot holds into the rock. Although he was then able to "free climb" the route as he dreamed, he was ridiculed out of Yosemite Valley for his poor form and blatant cheating. Today, his techniques continue to be regarded as extremely poor form. The first climber to truly free climb the Nose and achieve Jardine's dream was Lynn Hill. Her critique of Jardin is also a poignant reflection on the art of traditional free climbing: "[Jardine] failed to recognize that the spirit of free climbing is about adapting one's personal capacities and dimensions to the natural features of the rock, not the other way around."

Bouldering

Bouldering is a very simple type of climbing where climbers forgo ropes and climb short routes, usually of substantial difficulty. The only safety equipment is the bouldering or crash pad, a thick foam pad that absorbs some of the force of a fall from a short height. Bouldering routes vary in height from 5 to about 25 feet, and can involve only one or two moves or can be a long and complicated series of moves. Bouldering distills climbing into an art of movement and physical prowess. No expertise is needed, only strength, creativity, and stamina. Because the routes are so short, bouldering usually requires substantial physical exertion without rest, and the grading scale is much steeper than in standard climbing.

Originally, traditional climbers used bouldering to warm-up or stay in shape between long routes. Performance and the aesthetics of movement were of little concern to early climbers. John Gill, the "father of bouldering," changed this in 1960s by establishing difficult and acrobatic "problems" on boulders and outcrops. Gill was one of the first climbers to consider climbing boulders both an art and a sport in its own right. He also brought gymnast's chalk to climbing. John "Verm" Sherman invented the V-scale used to indicate bouldering route difficulty.

Below are several great videos of bouldering. In the first you'll see John Gill himself talk about the advent of the sport and see some footage of him executing the acrobatic bouldering moves that are now so prolific. The second video is footage of one of the hardest and longest problems out there, and the third is footage of Fred Nicole, one of the most aesthetic boulderers in the world.

Originally, traditional climbers used bouldering to warm-up or stay in shape between long routes. Performance and the aesthetics of movement were of little concern to early climbers. John Gill, the "father of bouldering," changed this in 1960s by establishing difficult and acrobatic "problems" on boulders and outcrops. Gill was one of the first climbers to consider climbing boulders both an art and a sport in its own right. He also brought gymnast's chalk to climbing. John "Verm" Sherman invented the V-scale used to indicate bouldering route difficulty.

Below are several great videos of bouldering. In the first you'll see John Gill himself talk about the advent of the sport and see some footage of him executing the acrobatic bouldering moves that are now so prolific. The second video is footage of one of the hardest and longest problems out there, and the third is footage of Fred Nicole, one of the most aesthetic boulderers in the world.

Free Soloing

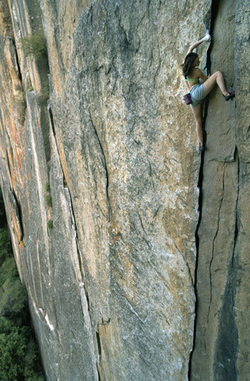

Steph Davis free soloing Outer Limits, 5.10c, Yosemite

Free soloing is climbing without ropes on a route where a fall will kill you. Alex Honnold, Steph Davis and Dean Potter are probably the most famous contemporary free soloers, both having free soloed big walls in Yosemite, Utah, Colorado, and Europe. John Bachar climbed throughout California in the 1970s and 80s and was the first climber famous for his wild free soloing. Bachar climbed many difficult routes in Joshua Tree and Yosemite, including New Dimensions 5.11a and the three pitch Nabisco Wall 5.11c. Famous for his high level of physical fitness and intensity in the Yosemite Camp 4, Bachar saw free-soloing as a way to establish dominion over rock and establish himself as the alpha male climber. While Bachar was known for his pride and personal fitness, the new generation of free solo climbers seems to be seeking something a little deeper with their climbing. Whether it is facing their fears head on, coming as close to death as possible and maintaining composure, or a the pure adrenaline rush, the motivation no longer seems to be "conquering" the rock as it was in Bachar's day.

The videos below have some beautiful shots of Alex, Steph and Dean free soloing and give some insight into why they do what they do.

The videos below have some beautiful shots of Alex, Steph and Dean free soloing and give some insight into why they do what they do.

|

|

|